The Ethiopian government may be guilty of atrocities against indigenous peoples as it completes construction of the Gibe III dam. UK aid-agency DFID has failed to exert its influence and protect the rights of these minorities.

Ethiopia may until recently have been a byword for famine, but in one part of the country at least, there are people who have lived largely without outside help for hundreds of years. With the connivance of the British government, this is about to change forever.

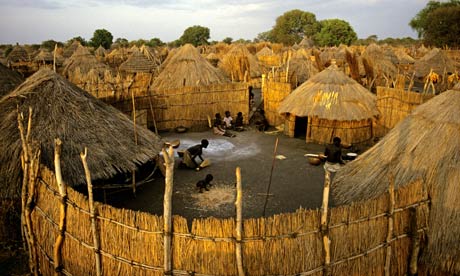

The tribes of the

Lower Omo Valley in south west Ethiopia - chief among them the Mursi, the Nyangatom, the Bodi and the Daasanach - depend on a combination of flood retreat cultivation on the banks of the Omo River, rain fed cultivation further back from the river, and cattle on the grass plains.

They move between these resources seasonally so as to exploit them to their best advantage. A self-sufficient existence outside mainstream society has meant that few speak Amharic, and that fewer still can read or write.

Like most of us they are strongly attached to their way of life and their traditions, and believe passionately in their right to decide for themselves whether and how to change them.

But flood retreat cultivation will become impossible when the Ethiopian government completes the Gibe III dam on the upper Omo, as it is expected to do shortly. Large-scale irrigation will follow, allowing government sugar plantations to gobble up huge swathes of their ancestral land.

At least ninety thousand people will be forced to relocate to permanent 'villages', compelled to give up their herds and become sedentary cultivators. If experience elsewhere in Ethiopia is anything to go by, many will end up dependent on government handouts or starvation wages on the plantations. A pastoralist way of life which has survived for centuries will disappear forever.

An unwelcome jibe

With no political clout, and no chance of redress through the courts, the Lower Omo tribes lack any means to protect themselves. But as the country's second largest donor, the British Government is not without influence in Ethiopia and could, if it chose, do much to ensure respect for their basic rights.

Unfortunately for the Mursi, the Daasanach and the other tribes of the Lower Omo, the UK's Department for International Development (DFID) has proved reluctant to act.

The UK knows there is a problem. With masterly understatement, it has acknowledged that 'past experience in other countries has shown that where people are resettled against their will this can impact negatively on their well-being and livelihoods'. 'Impact negatively' might well be interchanged with 'utterly destroy'.

In an attempt to avoid the worst excesses of forced resettlement, DFID and the other twenty-five aid agencies that make up the Development Assistance Group (DAG) have even produced a set of Guidelines for the Ethiopian government.

These stipulate that resettlements should be 'voluntary'; that they should take place only after a feasibility study has been discussed with the community; that the community itself should participate in the planning and implementation of the resettlement programme; that prompt and effective compensation should be paid for losses suffered; and that there should be an independent mechanism to resolve grievances and disputes.

But in the Lower Omo Valley these safeguards have been totally ignored. The gulf between what is written and what happens in practice has never been wider.

No feasibility studies were carried out before work started on the plantations. Thousands have already been removed from their land and herded into 'villages' against their will. More forced resettlements are on the way.

No compensation has been paid, and no system has been put in place to handle complaints. When an American observer suggested to a DFID representative in Addis Ababa that few of the Guidelines had been followed, she replied that 'none of them have been followed'.

Atrocities provoke apathy

The scale of oppression in the Lower Omo will probably never be known, but is at least partly described in a

report published in January 2013 by International Rivers.

The systematic violation of tribal rights in the Lower Omo is also charted in a petition that

Survival International has now lodged with the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights.

But none of this is news to the British authorities. As long ago as July 2009, Survival International met with DFID to express its concerns about the threat that Gibe III poses for the Lower Omo tribes.

In September 2011, Human Rights Watch told the Department that security forces relied on beatings, harassment and arbitrary arrests to crush tribal opposition to the plantations.

DFID was sufficiently concerned by the allegations - or at least by the political fallout that it might suffer if they became more widely known - that in January 2012 it sent officials to the area to find out for themselves.

At meetings with Mursi and Bodi they were told not only about the arrests and beatings but of the deliberate destruction of grain stores; of denied access to the Omo River; of threats to sell or kill the cattle of those refused to move; and of the widespread use of the military to intimidate people into giving up their land. There were numerous allegations of rape.

For several months DFID said nothing about these complaints in public, and so far as is known did nothing about them in private. It appears to have been spurred into action (of a sort) only when its interpreter on the January trip warned, in September 2012, that in the continued absence of any progress, he would release his audio transcripts of the meetings. These give a graphic account of the suffering that the tribes have had to endure.

Without Mursi

One Mursi man, for example, had asked: 'Now if you go to the Omo River ... will you see any Mursi there? We have left it without any people there and we are staying here in the plains being hit by the sun. The people were beaten away by the Government that brought its force.'

Another had complained that 'the Government never came here, and we didn't get to discuss with them about the sugar cane. They just went to the bush without talking to us, and looked at all the land, and then drove in their trucks and started clearing'.

A third had told DFID that Government officials 'come and take up all our land and give us violence, and they rape our wives. [They have done this to] the people of Bongo and also in the Bodi.

If they give us violence and we are killed off then they can take over the land. It will be taken over by the people who can read and write. To me, this is my land, the Mursi land, our ancestor's land.'

In October 2012 - shortly after it had been shown the audio transcripts - DFID prepared a so-called 'report' of the January visit. The report was undated, did not name its authors and did not explain the ten-month delay in writing it. The report was released only after Parliamentary Questions about the trip had been put to the Secretary of State.

Perhaps because DFID now knew of the transcripts, the report conceded that the allegations of human rights abuse were 'extremely serious'. It concluded, however, that a more detailed investigation would be required to 'substantiate' them, and that this would have to be based on a 'robust methodology'.

An investigation was apparently regarded as the necessary corollary to the equally 'robust' stand that DFID has taken, so the report claimed, towards the violation of human rights anywhere in the Lower Omo. There was no mention of the fact that ten months down the line none of the allegations had yet been investigated, or were likely to be investigated any time soon.

Perpetuating the abuses

More than six months on, we are no further forward. DFID and other DAG officials returned to the Lower Omo last November, but only to monitor progress on the sugar plantations.

More than a year and a half after they first learned of the allegations of rape, beatings and false arrests nothing has been done to 'substantiate' any of them.

In the meantime twenty six agencies have continued to fund a government which, for all they know, has not only violated repeatedly the fundamental rights of its most vulnerable citizens but has continued to do so with impunity.

A substantial chunk of these funds has gone to the Protection of Basic Services programme, without which the forced resettlement of thousands of tribal people probably could not have been contemplated.

An 'investigation' of the horrific events in the Lower Omo would have faced huge obstacles even if it had been conducted when news of them first unfolded.

The Ethiopian authorities would still have decided whom the DAG team would be allowed to visit and where it would be allowed to go. They would still have concealed any material likely to support the allegations, and allowed DAG access only to those officials thought to be sufficiently rehearsed in their protestations of innocence.

But an investigation now of abuses perpetrated in 2010 or 2011 would be a cruel farce. The physical evidence will have gone. Some of the victims of the worst violence will have died, and others will have disappeared.

Many more will fail to see the purpose of an 'investigation' that is too late to change anything: whatever evidence DAG might now unearth, it will do nothing for the thousands already expelled from their lands by intimidation, assault or worse.

DFID and its colleagues on DAG must be aware of all this. They must realise that it is now well nigh impossible to 'substantiate' the original allegations of multiple rape, land theft and arbitrary arrest in the Lower Omo - and that if they want to take a stand on the violation of human rights at all, they must form the best view they can on what they already know.

What they already know is that people from different tribes have given remarkably similar accounts, to different individuals at different times, of the methods used to evict them from their lands. The consistency of these accounts is a powerful testament to their truth, as is the absence of any obvious motive to lie.

They also know, if they have any understanding at all of the Lower Omo Valley, that none of its tribes would willingly give up their ancestral land or the cattle on which they depend to make way for someone else's sugar plantation. Why would they?

DFID knows too that the Guidelines that it has so laboriously put in place might just as well not exist. It knows that the Ethiopian government has conspicuously failed to enact into law the land rights supposedly guaranteed to pastoralists by the Constitution; and it knows that this is because the authorities in Addis Ababa believe that pastoralists are hopelessly 'backward', that they must be sedentarised for their own good, and that it is irrelevant that this is the last thing they want.

How politics trumps ethics

Had DFID really taken a 'robust stand', it would have concluded more than 18 months ago that the allegations of human rights abuse and forced resettlement in the Lower Omo were overwhelmingly likely to be true.

But this in turn would have required it to decide whether to suspend or reduce aid to Ethiopia until the government mends its ways. It has, or thinks it has, good political reasons not to do this.

In 2011 - the same year in which state violence began to spread through the Lower Omo Valley - the

UK pumped £344 million into Ethiopia. This was more than twice as much as it donated to any other African nation over the same period.

Payments on a similar scale in 2012 and in each of the next three years will give the UK a significant stake in the country's 'success'. DFID has no wish to upset the Ethiopian apple cart, or to abandon the millions of people likely to benefit from British aid who are not to blame for what has happened in the Lower Omo.

DFID may think that there will be no let up in the wholesale violation of tribal rights whether or not it pulls out. It may even have been persuaded by ministers in Addis Ababa that the days of the semi-nomad are over, and that they must not be allowed to stand in the way of 'progress'.

Above all, perhaps, the UK will worry that if it withdraws or restricts aid to Ethiopia as a mark of its disapproval, it will lose influence over one of the few stable regimes in a strategically important part of the world.

But none of these considerations are compatible with DFID policy. It has solemnly announced, for example, that a core 'vision' of its aid programme for the country is 'to protect the most vulnerable Ethiopians'.

The most vulnerable, however they are defined, must surely include the tribes of the Lower Omo, and their 'protection' must at least include the protection of their right to exist.

DFID is equally committed to the four 'partnership principles' that underpin all its development programmes, one of which is that countries which accept British aid must in return respect the human rights of their citizens. If the money continues to flow while this is persistently ignored, this principle is stripped of any meaning.

What is more, as a signatory to the

Vienna Declaration, the UK supports the rule that a desire to 'develop' tribal groups cannot justify the abridgement of their basic rights.

The UK wants to avert, if it can, a collision between the principles that it has officially endorsed and what it sees as the realpolitik of Addis Ababa. The pretence that DFID or DAG will eventually conduct some sort of 'investigation' in the Lower Omo, and that in the meantime business must continue as usual, fits the bill admirably.

By the time any report is produced one of the tasks in question - the annihilation of a pastoralist way of life and of the people who live it - will almost certainly have been accomplished. DFID will shrug its shoulders and move on. What else can it do?

There is plenty of long grass in this part of Ethiopia - or at least there was, until the earth moving equipment appeared on the scene - but none as long as the grass into which DFID has firmly kicked the tribes of the Lower Omo.

These victims are some of the many minorities that Survival International lobby on behalf of. For more information visit their website

here.

Gordon Bennett is a barrister in Lincoln's Inn (one of London's four Inns of court), and has extensive experience of the legal problems of indigenous peoples.

He is the author of 'Aboriginal rights in international law', and has given legal advice to Survival International for over 30 years.

He has worked on a number of landmark legal cases involving indigenous people: he was lead counsel, for example, for 189 Kalahari Bushmen in their historic lawsuit against the Botswana government, which for the first time established the principle of native title in Africa.