The Indian

Land Grab In Africa

By GOI Monitor

20 December, 2011

Goimonitor.com

Joining the neo-colonial bandwagon,

Indian companies are taking over agricultural land in

African nations and exporting produced food at the cost of locals

Indian companies venturing abroad is always regarded as a healthy trend, an indicator of India's new-found economic status. But little is known about how these companies are flexing their imperalistic muscles in poorer countries, grabbing the land and giving little in return. A report ‘India’s Role in the New Global Farmland Grab’ by researcher Rick Rowden brings forth these atrocities which are shockingly similar to what India used to blame rich western countires for.

Joiing the race with China, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, South Korea and the

European Union, Indian and Indian-owned companies are acquiring land in Africa at throwaway prices, indulging in enviornmental damange and exporting the food while locals continue to starve. The origin of this unhealthy practice can be traced back to the food crisis of 2008 when rich countries were forced to confront the reality of how fragile the global food scenario can be, especially for those without sufficient cultivable land. To ensure more direct control over food, these countries started acquiring land in poorer African countries and shipping the produce back home. A recent World Bank report found that 45 million hectares of large scale farmland deals had been announced between 2008 and 2009.

The initial support to such forays was based on the belief that the world is facing scarce food supply because of long-term under-investment in the agricultural sectors of many developing countries. However, as stressed by the

United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Right to Food, "the diagnosis and remedy are incorrect…Hunger and malnutrition are not primarily the result of insufficient food production; they are the result of poverty and inequality, particularly in rural areas, where 75 per cent of the world’s poor still reside.”

Outsourcing farming, the Indian way

There are various factors driving the “outsourcing” of domestic food production in India. Primary among these are stagnation or drop in crop yield due to "green revolution fatigue”, government’s concerns related to long term food security besides the allure of much cheaper land and more abundant water resources in African countries. The subsidies being offered by governments of African countries is another enticement. In many cases, the companies have been offered special incentives, including the offer to lease massive tracts of arable land at very generous terms with access to water and the ability to fully repatriate the profits generated.

According to figures provided by governments of various East African countries in 2010, more than 80 Indian companies have invested around $ 2.4 billion in buying or leasing huge plantations in Ethiopia, Kenya, Madagascar, Senegal and Mozambique to grow food grains and other cash crops for the Indian market. The high input cost of farming is also driving these companies to explore Africa. Talking to news agency IANS earlier this year, S.N. Pandey, an executive with Lucky Group, one of the companies which have invested in Africa, stressed on the price factor. “The cost of agricultural production in Africa is almost half that in India. There is less need for fertiliser and pesticides, labour is cheap and overall output is higher,” he was quoted as saying.

Indian agriculture companies also complain that India’s small and fragmented land holdings are unsuitable for large-scale commercial farming, and there are too many bureaucratic hurdles to investment. Recent offers by African governments allow Indian farmers to acquire much larger tracts of contiguous land on lease for 50 years, and in some cases even up to 99 years at throwaway prices. According to a news report in the

Indian Express, “The land lease rate in Punjab’s Doaba region is a minimum of Rs 40,000 per acre. In contrast, in most African nations, the land lease rate in terms of Indian currency comes to Rs 700 per acre. This means that for every one acre in

Punjab, Indian investors can own 60 acre in Africa. With a per capita land holding of 1.5 acre in Punjab, agriculture is ceasing to be a sustainable activity.”

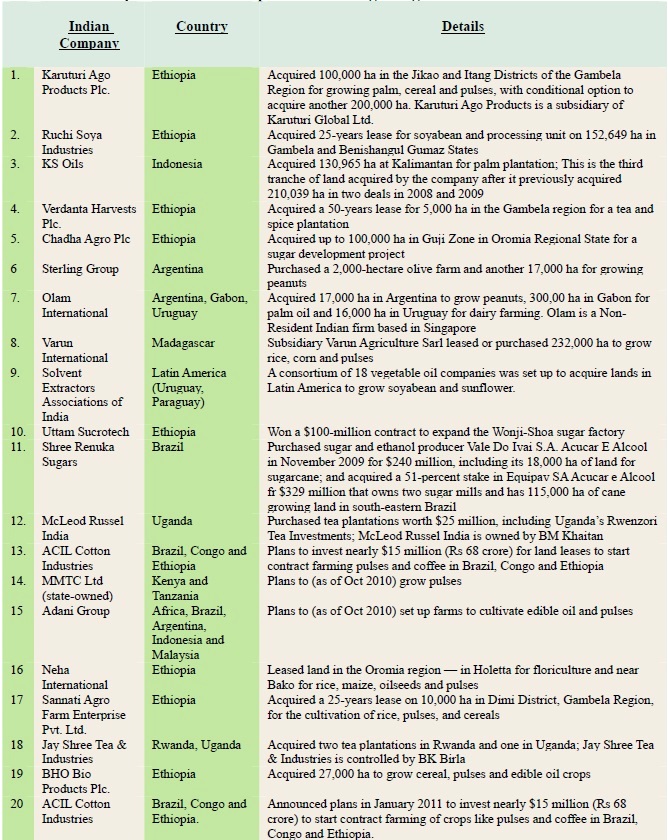

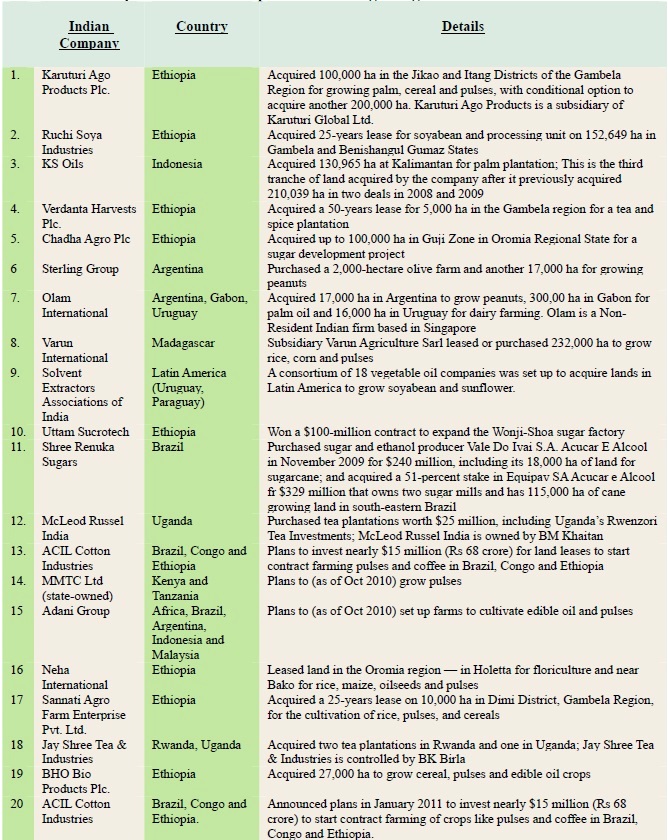

A sample of Indian companies investing in agricultural land overseas

Nobody bothers about locals

In some countries such as Ethiopia, where there is a lack of effective governance and democracy, local populations have reportedly suffered evictions with no recourse. Of all the land-grabbing deals in recent years, perhaps none has received as much attention as that of Karuturi Global's massive land leases in Ethiopia’s

Gambela region. While the East African country claims the entry of foreign investors would help develop the large tracts of wastelands, experts say there is no such thing as “waste or idle land” in Ethiopia, or anywhere in Africa.

Several studies have shown that local competition for grazing land and access to water bodies are the two most important sources of inter-communal conflict in most parts of Ethiopia populated by pastoralists. Indeed, in almost every case of recent land leases involving foreign enterprises, locals have complained that they lost access to grazing land and water due to these projects. This has also been the case, for example, with foreign investments in both the Bako and Gambela regions of Ethiopia where many Indian firms operate. Proponents of the new land rush also often claim that the foreign investments in land will create jobs for locals, improve living conditions and increase national GDP. In Ethiopia, over 3 lakh families have been potentially displaced but only about 20,000 people are expected to get jobs on the new highly-mechanised farms.

According to a news report on BBC online, “there have allegedly been a number of arrests and killings of local people who oppose the recent land investments.” The indigenous Mazenger people of Gambela have been struggling to protect their ancient forest-covered lands along tributaries to the White Nile that have come into conflict with the lease given to the Indian company Verdanta Harvests Plc., which plans to clear their land and use it for a tea and spice plantation. According to the documents available with Solidarity Movement for a New Ethiopia (SMNE), the locals were made aware of the plan to lease out their ancient lands and “secret forests” only in early 2010. They approached the Ethiopian President

Girma Wolde-Giorgis, who mostly has representative powers, and won his support. The Environmental Protection Authority of Ethiopia (EPAE) also recommended that the lease project be stopped since the short-term benefits of leasing would not outweigh the long-term costs to the country. However, the local Governor announced that the 3,000 hectare of forests had already been leased out for 50 years. Despite another intervention by the President, the project is moving forward and the forests are being cleared.

“If what is going on in Gambela was happening in

New Delhi, India, or in Oxford, England, Bismarck, North Dakota, or in Saskatoon, Canada, this would be unthinkable. If it is not allowed in these places, why is it justified in Ethiopia," asks Obang Metho of SMNE.

Environmental concerns and contracts

One of the most significant concerns about the trend of overseas investors relates to environmental impacts of establishing increasing numbers of large-scale, mechanised mono-cropping farms that are dependent on high levels of water usage besides heavy doses of pesticides and herbicides which impact both the soil and the underground water. “The ecological sustainability of land and water resources is an important concern, especially considering the relatively short-term orientation of the foreign investors versus the long-term outlook needed in considering the environmental impacts of land uses,” says D Byerlee, who presented a paper on “Drivers of Investment in Large-Scale Farming: Evidence and Implications,” at a World Bank conference in 2009.

Amid growing controversy around investments in Ethiopia, the Ethiopian Minister of Agriculture and Rural Development recently made public the 12 Land Rent Contractual Agreements for land leases including five contracts with Indian companies. All these contracts specified that the companies were to ensure that environmental impact assessments were undertaken and submitted to the authorities shortly after assuming operations and that the investors would otherwise abide by current Ethiopian conservation laws. They did not specify who exactly would undertake the environmental impact assessments, the quality and scope of such assessments and transparency of the process by which they are to be undertaken. Regarding water usage, each of the five contracts specified that the companies had the right to build dams, water boreholes and irrigation systems as they see fit. Only the smallest contract for Verdanta Harvests PLc.’s tea plantation did not mention water rights. Interestingly, only the biggest contract for Karuturi Agro Products Plc. included the additional clause that the company also had the right to “use irrigation water from rivers or ground water.” However, there was no mention of payment for this water usage, the quantity of water to be used and over what period of time.

All five contracts stated that the Indian companies have the “right”- not the obligation- to provide power, health clinics, schools, etc. It was not specified to whom these services might be provided –the local population or just the company workers. Yet, the provision of such facilities had been a high-profile claim made earlier by the government as to why the investors should be allowed to undertake these projects. None of the five contracts of the Indian companies mentioned labour laws or specified any wages or working conditions for their local employees. Nor did the contracts seem to justify the claim made by the companies and government regarding the increase in agricultural productivity and transfer of such new technologies to local farmers. If the omission suggests that the Indian companies alone shall retain the higher value technology, it is unclear how this will help local farmers in Ethiopia in the future.

Indian government's role play

Following a 2009 visit by Namibian President Hifikepunye Pohamba, the then Minister for External Affairs Shashi Tharoor said: “We are now in talks with Namibia after their President's visit, to use land for our purposes.”

At the sixth Agriwatch Global Pulses Summit in New Delhi in 2010, India's Food and Agriculture Minister Sharad Pawar asked the delegates to ponder over the “viability of Indians leasing land abroad for growing pulses and exporting it back to India.”

Both these statements point towards India's objective to ensure food security by acquiring land in lesser developed countries. The Indian government acts as a facilitator to the whole process rather than the main player. It is supporting the conventional new greenfield foreign direct investments, merger and acquisition purchases of existing firms; public-private partnerships ; specific tariff reductions on agricultural goods imported to India through the negotiation of regional bilateral trade and investment treaties and double taxation (avoidance) agreements.

Another major way the Indian government has financially facilitated the process is by giving concessional lines of credit to various developing country governments, banks, and financial institutions, as well as to regional financial institutions, through the Indian Export- Import (Exim) Bank. Often such lines of credit are for the purpose of national development projects and where these projects involve agricultural development, Indian foreign investors stand ready to win concessions and contracts for agricultural development in the form of their foreign direct investment.

The largest single line of credit approved by the Exim Bank so far has gone to Ethiopia ($ 640 million) for its Tindaho Sugar Project and it is also widely expected to facilitate Indian investments. The soft loans, with an annual interest rate of 1.75 per cent, are to be repaid over 20 years.

In trade policy, a number of economic incentives such as duty-free tariff preference schemes have been put in place by the Indian government in order to encourage private companies to invest in land abroad. For example, Ethiopian farm produce entering Indian markets is now taxed less than produce from India, according to Anand Seth, the deputy director general of the Federation of Indian Export Organisations.

The defence put up by companies

Indian companies reject their characterisation as neo-colonials and insist they are just doing business. Many companies claim the land acquisitions are simply strategies for their expansion and vertical integration. Raju Poosapati, the vice president of India's Yes Bank, which advises Indian investors in Africa, said a government ban on non-Basmati rice exports had driven Indian companies to go abroad in order to be able to grow and sell it in global markets.

Karuturi Global Ltd. clarified that it pays its workers at least Ethiopia’s minimum wage of 8 birr, and abides by Ethiopia’s labour and environmental laws. Speaking to Bloomberg, Sai Ramakrishna Karuturi, founder and head of Karuturi Global Ltd., said, “We have to be very, very cognisant of the fact that we are dealing with people who are easily exploitable,” adding that the company will create up to 20,000 jobs and has plans to build a hospital, a cinema, a school and a day-care center in the settlement. “We’re going to have a very healthy township that we will build. We are creating jobs where there were none,” he said. However, Metho says so far there has been no sign or mention of any of this according to reports from the local people.

The situation seems quite similar to what foreign corporates are doing in tribal areas of Orissa and Chattisgarh in India. Metho believes a close coordination between Indian and African activists can help serve the cause of marginalised communities in both the worlds.

The research report ‘India’s Role in the New Global Farmland Grab’ can be accessed here

5 comments

5 comments 5 comments

5 comments